And a Dream Deferred

|

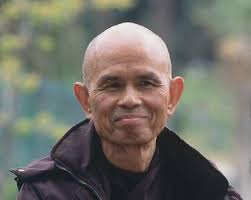

Image from cloudcottage.org

|

There’s a group at work trying to award my Sensei the Nobel Prize for Peace for which he was nominated in 1967. I couldn’t be more thrilled!

Anyone who’s read my posts over the years knows that the spiritual teacher I quote more than any other is the Vietnamese Zen Master Thich Nhat Hahn. I think he’s an extraordinary human being, a unique embodiment of peace and tranquility. He also has some of the most venerable company one could hope for: none other than Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

When Dr. King first started doing his landmark civil rights work in the United States, his focus was on racism and poverty. Although his nonviolent philosophy caused him to regard the Vietnam War as an exercise in madness, he had been warned not to take on the anti-war label. Many of his supporters believed that this singular hot-button issue would alienate key supporters and detract from the civil rights struggle. It wasn’t until after King had met Thich Nhat Hahn that he began to see racism, poverty and war as “the three-part scourge of humanity.” When he learned of the suffering of the Vietnamese people, he began to recognize it as inextricably linked to the struggle of people of color in the United States.

Nhat Hahn was a young monk in Vietnam in an area that had been under continual bombardment from the Viet Cong, the South Vietnamese, and the Americans for years. He founded what would come to be known as “engaged Buddhism” in response to this crisis, arguing that it was immoral for monastics to sit in the monastery meditating while people in the nearby villages suffered the effects of almost nonstop aerial bombardment. With a few other courageous monks and nuns, he founded his School of Youth for Social Services and went to where the bombs were falling to relieve the suffering in any way possible. Because he and his fellow monastics insisted that the war was the result of wrong perceptions -- refusing to take sides -- they were hated equally by those warring factions. Nhat Hahn saw friends blown apart by bombs; many of those friends were maimed or killed. He himself narrowly escaped death when a grenade was thrown through his window, bounced off the wall and exploded in an adjacent room. A few Vietnamese Buddhist nuns were so driven to despair and madness by the constant violence that they self-immolated. He knew something needed to be done quickly, and saw a potential strong ally in Dr. King.

In his letter, he told the civil rights leader that his people saw him as a Bodhisattva, a “great, enlightened being.” He wrote of the suffering of the villagers, and pleaded with Dr. King for his help, saying that many of the seeds of the conflict in his homeland originated in the United States. Still, he refused to take sides; he only wanted to stop the violence.

Dr. King met Thich Nhat Hahn, and was so deeply impressed by the man that he nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize. In his nomination essay, he wrote,

I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam. He is an apostle of peace...his ideas, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.

As a result of his outspoken resistance to the war, Thich Nhat Hahn was exiled from his homeland and eventually took up residence in the French countryside. He gradually gathered friends and fellow practitioners and established a community of practice known as Plum Village Mindfulness Practise Centre. In the ensuing decades, the community would train hundreds of monastics and provide retreats for thousands of lay practitioners. In addition to writing extraordinary books such as Living Buddha, Living Christ and Peace Is Every Step, Nhat Hahn has founded a monastic order known as the Order of Interbeing. He has also offered retreats specifically for veterans of the Vietnam War (both Vietnamese and American together) and for Palestinians and Israelis. At these retreats, he helps these people to understand that seeing the other group as the source of all their suffering is a delusion. Rather, he stresses learning to see members of the other group as human beings who also suffer. Ultimately, he says, our suffering is the result of wrong perceptions, a failure of compassion, and a lack of understanding that we are all inextricably linked as human beings. The suffering of one is the suffering of all; the happiness of one is the happiness of all. This fundamental rejection of dualistic thinking lies at the heart of all his philosophy and instruction. It has relieved a great deal of suffering and has helped to thrust the message of mindfulness onto the world stage.

We recently celebrated the birthday of Dr. King. In honor of his legacy and his unfulfilled dream of seeing Thich Nhat Hahn awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the international group Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) has set about trying to make that happen. Nhat Hahn is now 86, and still teaching around the world. I share the group’s vision to honor both Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and “this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam” during the latter’s lifetime, and I invite you to join me! Please click here for more information: http://forusa.org/blogs/for/thich-nhat-hanh-for-nobel-your-nomination-for-for-peace-prize/11761.